Author: Rizwan Ahmed Memon

My son, Wajdan, had given me two different kinds of medicine that claimed to induce a deep, relaxing sleep, but after taking both, I still didn’t feel the slightest bit drowsy. My chronic back problems had flared up, and I couldn’t even bend down to touch my own feet—a problem that comes with old age. Living at home was awfully lonely; hardly anyone would ever talk to me. This endless loneliness had only added to my health problems, and haunted every waking hour.

“Now lie down on your bed, Kurara, and let the medicine take effect,” my son said while leaving the room. “You won’t be alone anymore; I have spoken with the manager of the local nursing home. They will probably come to take you there tomorrow,” he closed the door.

I shook my wrinkled head in resigned affirmation, thinking to myself, “A nursing home sounds good.” I was sick of the loneliness I felt at home, so going to a nursing home would somehow alleviate the feeling, I thought. Taking off my thick, heavy glasses, I looked into the large oval mirror on the dressing table, and placed my glasses in their usual spot. The closed off room was as silent as a graveyard, and felt completely disconnected from the bustling streets just outside. The silence was like a venom gradually devouring the already tattered fabric of my heart, and the oppressive height and weight of the surrounding walls closed in around me like the ravenous mouth of some cruel lion, preparing to swallow me whole.

I looked in the mirror at my pale, longing eyes, starved in their desire of many years to see my wife Rubab and the streets of my native village. Overwhelmed by my desire to see her, and the oppressive atmosphere of solitude, I collapsed on the bed.

As I had feared, the same flashbacks recurred. My memories of Rubab flickered like a film to which I alone was its audience. The echoes of cries resounded in the background of my mind, and my old, native home gradually surfaced before the eyes of my consciousness.

The medicine appeared to be useless even after an hour—I kept tossing and turning. However, far more effective than any medicine was that terrible, painful venom ruthlessly biting at my heart. The anguish it inflicted was a burden that I desperately wanted to share with someone so as to win some relief from its relentless onslaught. Yet, in that moment, my loneliness, disease, and desire trapped me in an isolation deeper than the solitary flights of a hawk on the hunt.

The lights of Karachi didn’t amuse me at all. On the contrary, my weak eyes ached from their brightness. The shopping malls, parks, and zoos had lost all their charm for me after the craze of youth, wealth, and lust had died down. All paled after realizing how much injustice I afflicted on Rubab. This city seemed well-suited for only rich, young men—not for a decrepit 75-year-old man like myself. I ventured only to the street downstairs. The long, winding stairs were difficult to descend, but I often felt suffocated in the house, and the open air was my only respite. I would sit by the street and watch people pass by. I felt lost in the commotion of the city; my heart weighed heavy with regrets. Wajdan didn’t have time to listen to me even though I had so much to tell.

Uncaring time assured the night passed, and in the pale morning, the home cook brought my breakfast. “Dada,” the cook entreated. “Eat your breakfast and get ready. Today you are going to the nursing home.”

I didn’t say a word. With hardly enough time to finish breakfast and change my clothes, there was no time to talk.

My son came. “Kurara,” he told me, his voice soothing, “Don’t worry. I’ll visit you every weekend. If you need anything, feel free to ask the worker or the cook. I’m leaving for work now; they will help you with everything.”

“Dada,” The cook inquired after my son had left, “Why does your son call you “Kurara? It is not a good word for father.”

“It means old,” I replied tiredly. “Am I not obviously old?”

The cook just looked at me in silence.

Shortly thereafter, a van came with a young doctor who greeted me as he stepped out saying, “Asalam-o-Alaikum, Baba.” His warm, humble manner touched my heart. When he approached me, he touched my feet and said, “I’m late, but I have finally come.” He spoke as though he had known me for ages. I kept looking at his face which resembled mine in the days of my youth: round with reddish lips. His hair was black and wavy, and his body was tall and sturdy as mine once used to be. However, his smile seemed more sincere than the one I used to have. “Baba, let me help you get into the van,” he said as he tenderly took my hand. His treatment of old people was kinder than mine when I was his age. “Don’t worry about anything. I’ll take all your luggage and put it safely in the van,” he said as he handed me my walking stick.

This doctor is more respectful towards me than my own son, I mused.

The young doctor took me to the nursing home, a three-hour drive through the thick traffic of Karachi. My new, four-bed room seemed cozier than my previous room. “This is your bed, Baba” he said, helping me sit on it.

Near my bed was the bed of an old woman, who during her waking hours, was permanently consigned to her wheelchair. “Ada, how do you do?” She smiled, her face was full of wrinkles, but she had a genuine warmth that made everyone instantly like her.

“How do you do?” I replied.

We chatted for a short time, until the pain in my back forced me to lay down.

While I was less lonely at the nursing home, I spent every day lost in my thoughts of Rubab. I could picture her clearly in my mind, sitting on the bed wearing her bridal dress. Almost a month passed, but my son hadn’t yet come to see me. The young doctor, however, came to see me every day.

“You seem to be brooding over something all the time. Would you mind sharing it with me?” asked the woman in the wheelchair, noticing my constant silence and sadness. “I have also observed no one visits you.”

“My son is a banker, so he is often busy. He will come one day,” I retorted.

“Everyone gets sick of old people. It is a hard truth,” she said.

Then I returned to my silent state.

Days kept passing, the roommates and I exchanged a little dialogue every day. I wanted to talk to the young doctor, yet, for some reason, I could never bring myself to do so.

One day I asked the woman next to me, “The young doctor who looks after this nursing home—What’s his name?”

“Rohet. He is a Hindu.”

“Ah, a Hindu?”

“Yes.”

“I don’t know why, but he feels like my own family.”

“Yes, he is a kind man like his mother, Rubab.” My eyes widened as I heard that name. I put on my glasses quickly and moved closer to the woman.

“Rubab? That is a Muslim woman’s name,” I added with astonishment.

“I don’t know,” my elderly roommate replied. “That’s what she told me when she came to visit this nursing home last year. But why are you so curious?”

Stepping back to my bed, I replied, “It is strange, you know! A Hindu woman has a Muslim name.”

“It is not that strange,” she shrugged. “There are many mysterious things in this world. For example, what can be odder than having offspring who send us to these nursing homes to die, out of sight and out of mind?”

I intently observed Rohet as he went from bed to bed visiting each elderly person in the nursing home. When he came to me, he said, “Baba, I will sit with you for a while. I know you want to talk to me.” He took my hand and asked me to walk outside. He asked me about my back pain and sleep schedule.

“I am happy here,” I replied. “My happiness increases when I see you. I don’t know why.”

He smiled and looked into my eyes.

“If you don’t mind, may I ask you something?” I asked, tentatively.

“Not at all. Please ask,” he encouraged.

“You are a Hindu, but your mother’s name is Rubab, a Muslim name?”

“Yes, my mother is Muslim. I am also Muslim. It is just a name that my father gave to me.”

“Your father gave you a Hindu name?”

“He is not my actual father. He raised me. I mean, he did more for my mother and me than my biological father.”

“I don’t understand,” I replied, hoping he would tell me more.

“My mother once told me that she tried to commit suicide for some reason after the first night of her marriage. Feeling desperate, she actually jumped into the Rais Canal in Larkana. She was saved by Dr. Lal Chandar, the man who helped bring me up.” He seemed deep in thought. “My mother told me that her husband was not only unfaithful, but also physically abusive and violent. He shook his head, his smile returning. “Well, it is water under the bridge and a story long past. We don’t know anything about that man now.”

After hearing Rohet's story, I finally realized why it felt like he was my own family and why he seemed to resemble me so much: He was my own son. Coming to this realization, my hand, which Rohet had held in his hand, started to shake. My body trembled.

“Are you all right?” he asked.

“No. I am feeling cold; please take me back to my bed,” I replied brokenly. Fragmented words crumbled to pieces the moment they left my mouth. I did not know how Rohet managed to understand me. My back was hurting so much from the shaking that it was almost like I was attempting to lift the sky itself with every breath.

Back inside, Rohet helped me lie down on my bed and put a bedsheet on me, but still I was trembling. He brought two more sheets, but they did little to help me. It was early spring, yet I was shivering as if it were mid-winter. The realization that Rohet was my son rocked me to my very core.

Rohet stayed at the nursing home late that night until I fell asleep.

The next day, he came early and asked how I was feeling. I didn’t dare look into his eyes that day. I felt so ashamed of myself. I wondered how ashamed he would be, if he knew I was his father.

“How many siblings do you have, son?” I asked him.

Rohet smiled because I had never called him son. I always referred to him as “young doctor.”

“None, Baba. Mother never married after she left her husband’s home,” he replied while checking my pulse. “You’re fine now, just a little low blood pressure. I have prescribed some tablets; the nurse will bring them.”

I wondered if Rohet sensed that I had something to do with his life story, but if he suspected so, he didn’t ask. I was relieved that he didn't. I wasn't ready to admit my wrongdoings. And he probably didn’t want to hear anything more about his mother’s sad past.

The days continued to pass and my desire to see Rubab, to seek forgiveness, only increased. Now that I knew she was alive and within reach. I longed to speak with her before my last breath.

I had to fight an internal battle every day. I was uneasy with remorse and, in my desperation to find forgiveness, my mind and heart remained fixed on those I had wronged, on their innocence, and on my own personal feebleness. This fixation was like a taut rope binding me and draining my peace, my confidence, and even, ever so gradually, the waking alertness from my mind.

One night, in that mental and spiritual bondage, I fell into the darkness of sleep and had a dream. I had crawled to Rubab to search for my forgiveness, and for my freedom.

Her eyes tore into me, and she hissed, “Have you come to claim your bride?”

“No!” I blurted out with a mixture of shame and pleading. “Well, in a way. Let me explain.”

Before I could give my explanation, she had pounced across the room and lashed her palm across my face. One of her nails, long and jagged drew a line of blood across my face. Perhaps, because I was surprised by her sudden fury and perhaps because I believed that I deserved it, I let the full force of her strike seep down into the depths of my marrow. I let its force propel me onto the sofa and let its reverberation shatter the arrogance of my legs that fought to keep me standing pridefully. I crumpled to the ground, and before her, I was still and small, meek and humble, a perfect supplicant begging for compassion.

She stood above me empty of compassion and mercilessly rebuked, “Truth! I have no time and no patience for your double-talk and lies!”

My reply was soft and pleading, but cut with a subtle sullenness, “Are you mad, woman!” Please, please. I hoped you could forgive me.” My eyes filled with tears and I dared to lift myself to my knees, bringing my collapsed, broken shell into a prostration before her.

Though I had lifted myself up, I felt insignificant before the aura of her indignation. I was alone before her, only that bondage that had suffocated me into sleep was with me. She had as a companion her terrible wrath, which had made her boundless. I squealed piteously, “I’m not a bad man.”

“You’re a monster. Men have honor; you have none.”

I begged, “Please, please do not let me die with this crime on my heart.”

“Oh, it is God you fear! Where did your faith go when you bribed a mullah to allow you to rape a girl and steal a family’s honor? Your ferocious blunder closed all doors to me. I could neither return to the village nor stay at your home. I lost my family, my honor, my life, just so you could have sex.”

“Please, please. I didn’t know.”

“You never cared! And still you wish forgiveness to only win God’s mercy. God judges how you have lived, not upon the last-minute appeals a desperate soul pleads.”

My dream was still going on when the old wheel-chairwoman shook my foot. “Why are you sobbing? I think you are dreaming. Wake up, Ada.”

My eyes opened.

“Were you dreaming?”

“Yes,” I replied.

During the fever of my terror, sweat had become like a sea on my body, a sea that had made my body damp and soft as if my body were a vanishing paper boat being dragged down into the ever darkening depths of a jealous, grasping ocean.

I was frozen in terror for many days, and became undecided whether or not I should go to Rubab. I didn’t tell anyone about the dream.

During Rohet’s visits, I kept asking him about his life and his mother. Rohet didn’t know much about me, his biological father. Even after all my cruelty, it seemed Rubab had never complained about me. She had not told her son the complete story of his cruel father. I felt I was not only guilty of harming Rubab, but Rohet as well. I wanted to tell him the truth, but I did not dare tell him in person. I decided to write the whole story in a notebook and ask Rohet to take me to Rubab at least once before my last breath.

That evening, I asked Rohet to provide me with a notebook and two pens. “Are you going to write your autobiography, Baba?” His bright smile contrasted the darkness of my turbulent soul.

“Yes. But do not try to read it until I finish it,” I said firmly.

“Okay. I will be waiting. I am sure it will be interesting!” he said with a fading smile.

“Son, I am worried about one thing,” I looked down.

“What is it, Baba?” he asked, tension on his face.

“I feel you will hate me after reading my autobiography!” I lifted my head and looked at him.

“No, I’m sure I will not. What on earth makes you think that?” he asked.

I sunk into silence until sorrow prompted me. “Son, promise you will like me the same way after reading my story,” I pleaded.

“Of course I will,” he promised.

I was sure he knew my secrets were about his mother. I was doing a horrible job of hiding. He still didn't ask me anything about her. Perhaps he was simply respecting my privacy, or better yet, he did not want to disturb my declining health any further.

The next day, I started writing my story:

“It was summer. On the day of the wedding ceremony of my brother, Hyder, my father had arranged a separate dinner party for village women in the city. My mother had forgotten her night-time glasses at home, so my father sent me to the dinner party with the glasses. While talking to my mother, a fairy-like girl with reddish cheeks, hazel eyes, and dark hair arrived. Her eyes were a gorgeous ocean, deep enough to drown you in their beauty.

“Jalal, this is Mrs. Nihaal. And this is Rubab, their first daughter.” My mother introduced her to me.

“Asalam-o-Alaikum,” Rubab gently greeted me. She was extremely enticing, and quickened my pulse.

“Rubab, Jalal is the second son of Mrs. Khuhro,” Rubab’s mother explained.

“Yes. He wants to study law,” continued my mother.

“Nice to meet you,” Rubab said gracefully.

“It is great to meet you. Do you study anything?” I managed to inquire.

Rubab looked down.

Her mother spoke instead, “No, she doesn’t. We don’t let our girls get higher education—just up to grade ten. It is the rule in most Mirbahar families. Rubab, go and chat with the other neighborhood girls.”

I left the dinner party, my mind filled with visions of the lovely girl. Rubab seemed very docile, but a pure beauty. I had always treated beautiful girls as “sex toys.” I wanted to have Rubab on my bed as soon as possible at any cost.

My father was a police officer, and people feared the Khuhro family because of their power. I thought I could use this fear in order to capture Rubab. Though barely an adult, I had already slept with several women. Rubab seemed to be more beautiful than any of them. I didn’t know how I could sleep with her, but I could not check my blinding desire. My father’s power had lessened my fear for the consequences of my actions.

Within a week, I collected some information about Rubab. She never went to the city alone, so it was impossible to kidnap her. She didn’t have a phone, so she couldn’t be embroiled on the phone in the net of my unrelenting lust. There were only two options for me: either arrange an attack on her home at night, or marry her.

I shared my feelings with my friends who often arranged for prostitutes in a hotel. “I met the hottest girl any of you have ever seen. I just want her to be in my bed.” I told my friends everything about Rubab’s family. “She belongs to a Mirbahar family and she has a brother, Gulab. He works in the guava orchards in winter and cuts wood in the summer.”

My friends suggested that I give Gulab money. We decided that we would invite him to the Otaq.

The next day, Gulab came and greeted us nervously. “Saeen, is everything all right? You have called a poor man to your service.”

I looked at him with wide eyes. “Your sister has grown up and I have heard that she is still not married!”

“Saeen, she has just completed tenth grade. It is a matter for our elders to think about her marriage,” Gulab replied.

I didn’t know what to say, so my friend told him, “Jalal wants to marry your sister, so make arrangements without any delay. This marriage will be a secret. His parents want him to marry a rich girl, but he wants to marry a girl from a poor family. He believes a poor, simple girl will prove to be a good wife, compared to the rich girl. He believes his parents won't force him to marry the rich girl if he has already consummated the marriage, and maybe have a son on the way before they learn about it. Your sister will not live in the village; she will stay at Jalal’s house in the city.”

I looked at my friend and was amazed to hear what he said. “Tell your parents to keep this marriage secret for about six months.”

Gulab seemed hesitant.

“You will be given a lot of money,” my friend added.

Greed sparked interest in Gulab’s eyes. “I will tell you of my parents’ decision tomorrow at this time.”

My friends told me the rest of the plan after Gulab had left.

“What a tangled web we have woven,” I said to my friends. I was so lost in the madness of my lust that I didn’t know what I was doing.

Gulab returned the next day, “I have made my parents agree to your conditions. Who can be a better husband for our sister than Jalal? We have decided to make this marriage happen as soon as possible.”

It seemed to me that Gulab’s family was poor and they probably thought that Rubab would be living the life of a rich wife if they gave her hand to me. They didn’t have a clue of our plans. “That’s great. This marriage will take place on Saturday next week in the city,” I said to him and gave him some money. “Keep it secret! Saturday evening at this time a car will be sent to you. Do not bring any relatives. Just your family.”

Everything was going as we had planned. The car brought Rubab’s family to the house which we had rented. It wasn’t my house.

We had bribed a Mullah, religious person who performed the Nikah tradition.

“Puta, Rubab is a young girl and very shy. I have made her understand everything,” said Rubab’s mother. “Please don’t be quick or angry with her. Let her take time to understand the things of married life. I’m sure she will prove to be a good wife.”

“Yes, Aman,” I said to her.

By 9 pm. Mullah and my friends had left, and Rubab’s family stayed in a room. I went to the room where Rubab was waiting for me. “You are a such a hot girl,” I said to Rubab. I had said the wrong thing, but I didn’t realize it at that time. “I couldn’t sleep well after that day when I saw you at my brother’s wedding. I had to marry you to fulfill my desire. Girls are nothing to me, just ‘sex toys’.” Worried and pale, she looked at me. I started to take off my clothes. She became nervous.

“I cannot wait anymore. I hissed, “Take off your clothes!”

She started to cry.

“There is no need to cry; you’ll enjoy it.” I forcefully took her clothes off and started to kiss her…

By midnight, I had become too tired, so I just lay on the bed beside her. I told her the whole plan that we had made to sleep with her.

“You have destroyed my life, my whole family. I believed my parents, and acted upon what they said,” Rubab cried. She kept weeping. She wept so much that I thought she might flood the whole house with her tears. An endless rain poured from her eyes. She might never stop, I thought.

In the morning, Rubab’s family was amazed to see Rubab so distraught, but she remained silent on matters between us. Perhaps, she didn’t want them to be worried. She probably thought that they wouldn’t be able to bear the injustice done to her, so she kept quiet. Her family decided to leave for the village. “I will come tomorrow to see Rubab,” said Gulab.

In the evening, I called my friends over. “I didn’t sleep at all last night. You’re not gonna believe this: I did it five times!” I bragged. “Tonight, it is your turn!”

Three of them decided to go to Rubab that night. I didn’t feel bad at all. It was what we had decided. Pleasure before all else! I told Rubab that she would be dealing with my three friends that night.

Rubab’s tears had dried. I could tell she was thinking about something, but I couldn't figure out what. I thought nothing of it. What could she possibly do? “We will be back by 8 pm. Don’t worry about anything,” I said to her. We locked the door to the house and went out to drink some wine.

We came back late. The door of the house was locked as we had left it, but Rubab was nowhere to be found. She had somehow climbed out the window and ran away. We tried to look for her on the road, but we couldn’t find her.

The next day, we told Gulab that Rubab had run away. Poor Gulab was beside himself, crying, “How could you do that, Rubab? You have dishonored us.”

My friends and I told him not to tell his parents anything, otherwise they would not be able to bear such a degrading act by their daughter. We told him to say that she was very happy in her new house and didn’t want to come back to the village, and that Jalal would move to Karachi with Rubab very soon.

I continued giving money to Gulab for some months. When I moved to Karachi for my education, I didn’t go to the village anymore. Rubab’s aged parents kept lying to the villagers claiming Rubab was married and lived in the city of Karachi.

A few months passed and I did not hear any more about Rubab or her family. I married one of my classmates after completing my degree and a year later we had a son. I didn’t continue my studies in law after my graduation, but my wife went to the US for her doctorate degree after seven years of marriage, leaving Wajdan with me. However, she never returned to Pakistan. We had never gotten along very well, so I did not miss her very much. I hoped that she was doing well, even though she never sent any signs she was even alive. I assumed she must have found a better life for herself in the US. I studied law, but I never practiced justice. Law or Lord could never justify my actions against Rubab. Money and lust had blinded me.”

I ended my autobiography in the notebook with that admission.

Three days later, Wajdan came to see me. “I’m really sorry. I couldn’t tell you. I went to the US because of an emergency. Mom tried to commit suicide by jumping from the second floor of her apartment. She was in a coma for almost two months and died. Uncle Anas, one of her best friends she had been living with, gave me this letter for you. He said it was her last wish to somehow get this letter to you. I didn’t inform you because I knew you couldn’t go there.”

I silently listened to him and he put the letter in my hand. Rohet came in and Wajdan became engaged in conversation with him. I put the letter under my pillow to look at later.

During the night, I opened the letter:

“Dear Jalal,

I cannot find the words to start this letter. My pen shakes and my tears wet the paper. Now that I see my death approaching, I don’t want to die with regrets and the truth withering with me. I want to tell you a secret that has made me ashamed of myself for years.

Your son, Wajdan, is not your son. He is the child of Anas, our university classmate. I had an affair with him before I married you. After marrying you and owning enough of your wealth, Anas and I made a plan to move to the US. I didn’t come here for education.

If possible, please forgive me. I cannot say enough how severely this pain in my conscience has been weighing me down. I cannot forgive myself for this. I want to punish myself; because I cannot live anymore with the torment of my conscience. I am going to end my life, but before my last breath, I wanted to seek forgiveness from you and tell you what I had done.

Eternally sorry,

Maria”

After reading her letter, I wondered at how the universe works. I wronged someone else’s family and someone else wronged my family. I pondered over God’s predefined rules: as you sow so shall you reap.

The next day, I said to Rohet, “Son, I want to meet your mother. Will you take me to her just once, please?”

“No problem, Baba. I will take you to my home this very evening.”

Later, Rohet and I went to his home. As I entered, a familiar fragrance from long ago roused my nostrils. It was an absolutely delightful scent, amber, with tones of vanilla and musk, mixed with sandalwood and jasmine, finished with a fruity citrus. A scent familiar, yet unknown. Led by the sweet aroma, I recalled the fragrance. It was the perfume Rubab wore on her wedding night. A rush of shame shot through me. I stayed at the door of the veranda and watched as Rohet approached his mother, who was coming from another room, and touched her feet.

“You are home early today?” she said.

“Yes. Someone has come to meet you.”

Rubab looked at me from a distance. She was wearing a hijab, and her hands were covered by gloves, more religious than I remembered. She recognized me at the very first glance. She took some steps towards me very slowly, gazing at me through her white glasses and taking her gloves off. I feared she would slap me or spit in my face out of her severe anger, and Rohet would have me expelled from the nursing home. As she reached me, Rohet said, “Mother, this is Baba. He has lived in the nursing home for the last eight months. I am sorry I have never asked his actual name. I just call him Baba.”

“He is your Baba, Rohet,” Rubab replied to him, still gazing at me.

Rohet didn’t seem to understand what she said in that simple, pregnant sentence. He appeared baffled by her words.

“I will be back after I take a shower. Please sit and chat,” Rohet said to us, quickly changing the subject and leaving for his room.

Rubab slowly moved her hand towards me for a handshake while saying, “I knew you’d come eventually!”

I saw the same ring that I had given her on the Nikah day on her finger. I didn’t feel pure enough to shake her hand. I felt myself so polluted that I didn’t dare to touch a woman, a woman as spotless as an angel.

She took my stick, held my hand in hers, and asked me to come inside. I sat on the sofa, and without my asking, she went to bring a glass of water for me. She had grown so old that her hands shook as she served the water. I studied her from head to toe. She seemed to be still as pure as when I first saw her at my brother’s wedding.

I drank the glass of water and remained silent. She gazed at me for a while and said, “Forgive me for leaving your house. I could have remained your ‘sex toy’ forever, but I would rather die than be that toy for your friends. I jumped into the canal, but I was saved by an angel, Lal Chandar. This person has never tried to even touch me, ever. I told him that I am the property of someone else, and that I am married. He is a Hindu, but respects humanity more than some Muslims.”

I felt the shame of her reference. I was that Muslim. I didn’t respect humanity. I always used people for my own pleasure and benefit.

She continued, “The only person who has touched me in in that way, is you. Rohet is your son. I became pregnant after that night.”

I silently listened to her and had no words to speak; the only sentence that I could utter was: “Can you forgive me, Rubab?” Tears poured from my eyes. This was my moment to finally receive the forgiveness I had been longing for. “If you will forgive me, I hope God will also forgive me.” I was sobbing. I didn't know what I would do if she could not find it in her heart to forgive me, but I knew that I wouldn't forgive myself for what I had done.

She took my hands gently and put them on her eyes. “The prophet (Peace Be Upon Him) said, ‘If I were to order anyone to prostrate to someone other than Allah, I would have ordered the woman to prostrate to her husband.’ As God forgives you for what you have done, so shall I. You are my worldly God. I will be yours until my last breath.”

I burst out sobbing. Finally, I had been forgiven! The feeling I was experiencing was bittersweet. On one hand, how could she have forgiven me after committing such an atrocious act? On the other hand, I was unbelievably grateful that she was so kind-hearted and wonderful that she could find the room to forgive someone even as cruel as I had been to her. I did not deserve her kindness. Rohet came rushing toward us with a look of understanding. He asked us not to cry. His mother, sobbing said, “Your father has come home to us!”

“I want to spend the last days of my life with Rohet and you, Rubab,” I said.

“I want to live with you, too. And I want you to take me back to my village, to my family,” Rubab said.

“I’ll take you back home and tell everyone of your purity.”

The next week, we left for our village. Rohet came with us but would return to Karachi to look after the elderly people in the nursing home and to read my appalling autobiography that I left in the notebook for him. I couldn't have asked for a better ending.

After a month, Rohet wrote me that he read the notebook, and that he forgave me, even after all the horrible things I had done. “If my mother can find the room in her heart to forgive you, I can too,” he wrote. Rohet was very kind like his mother, maybe he realized I had changed and was no longer like my younger self.

I believed God had forgiven me too because He gave me the chance to seek forgiveness from Rubab and Rohet. Now, my last breath could be truly happy.

---------------------------------------

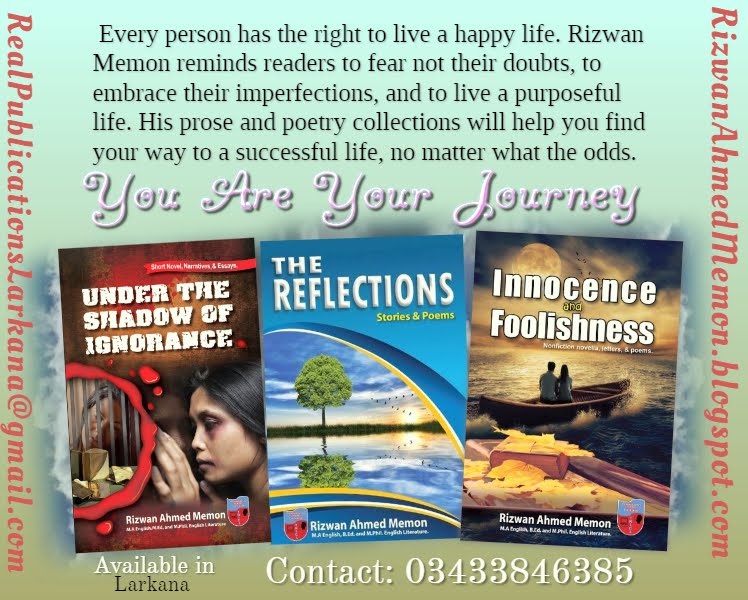

This is story is in my third book "Under the Shadow of Ignorance."

This is story is in my third book "Under the Shadow of Ignorance."

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Copyright © 2018

No part of this publication may be reproduced , distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews.

----------------------------------------

For more stories, purchase Memon’s books:

“The Reflections,” “Innocence and Foolishness,” and "Under the Shadow of Ignorance."

“The Reflections,

The books are available at all bookstores in Larkana, Khairpur, and Sukkur.

You can also order the books by courier. For more information, contact at below addresses:

Email: RealPublicationsLarkana@gmail.com

WhatsApp: +923433846385

WhatsApp: +923433846385